Partnering for Preservation

Protecting Molokai’s Watersheds

An understanding of the connections between mountains and ocean — mauka and makai — is rooted in ancient Hawaiian culture. Today, invasive species and human impacts are threatening to clog Molokai’s reef — the most extensive coral reef in the Main Hawaiian Islands — with sediment washed down from the mountain slopes. Today, scientists are doing studies to provide proof of this evidence and offer their data to help find solutions. And today, Molokai residents are meeting together to discuss those solutions and taking action to protect the island’s most valuable resources — both the mountains and the ocean.

“You don’t simply get this [muddy water] after a rainfall,” said Jim Jacobi, an ecosystems research biologist with the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS), referring to the brown water frequently seen on Molokai’s south shore. “Erosion is a part of geology but understanding what is a normal… rate versus an accelerated rate from human impacts [is important].”

Jacobi shared his years of research in the Kawela area last week at a gathering of key participants in the East Molokai Watershed Partnership. A watershed is an area of land that collects ground water, essentially acting as a water source. Molokai has several watershed areas, and the Partnership consists of organizations committed to preserving Molokai’s water through conversation.

Connecting the Dots

As Jacobi’s and others’ research has shown, healthy plant growth can play an important role in minimizing erosion and preserving watershed areas. The Molokai Land Trust, for example, has been conducting a series of field tests in their Mokio Preserve, which contains the Kawakiu watershed in west Molokai. Executive Director Butch Haase presented his findings in before and after photos over three years showing dramatic regrowth of native species on pili grass bales in a fenced area in the preserve.

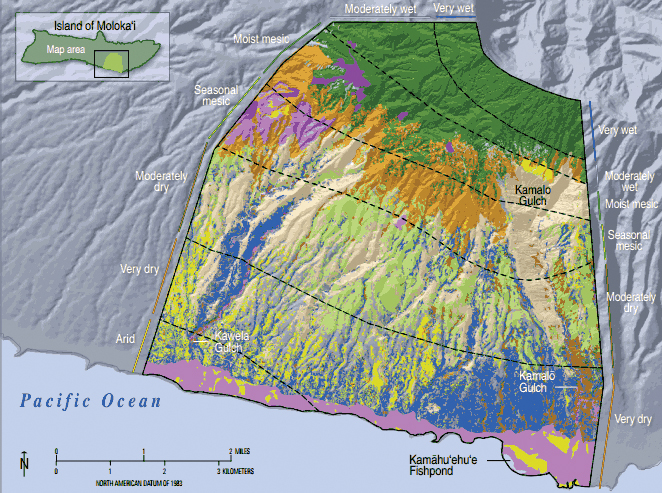

A vegetation map for the Kawela-Kamalo ridge-to-reef area. Dark green indicates Ohia montane wet forest, light green is mixed native shrubland, brown shows mixed native dry forest, blue is kiawe woodland with alien grasses, and tan indicates areas of little or no vegetation. Map courtesy USGS

Many natural resource managers have noted that ungulates — hooved animals — threaten watershed areas by eating vegetation bare, exposing soil to erosion. Scott Fretz, the Maui district manager of the Division of Forestry and Wildlife (DOFAW) said his division of the Department of Land and Natural Resources is in the process of strategic planning to cover a broad range of mandates, including forests and watersheds, wildlife and public hunting, fire protection, control of invasive species and trails and access. He said one of the plan’s major challenges has been conflicts of interest and goals in certain areas, particularly the balance between game management for hunting and the need for ungulate control.

“One of the most difficult issues is endangered species recovery versus hunting,” he said. “On Molokai, ungulates are more controlled in pristine areas and less controlled in game areas… Fencing is the only way we know of to keep game out of endangered species areas.”

In Kalaupapa, National Historic Park Chief of Natural Resource Management Paul Hosten noted that the absence of grazing within a fenced area on the peninsula has shown an increase of native growth in recent years, but the type of dominant species has changed. When the area of heavily grazed by livestock and deer prior to 2001, the low-lying native Hinahina plant was growing sparsely, but now, the more vigorous native Naupaka has prevailed.

Jacobi’s studies, which began in 2008, have also noted likely relationships between the presence of ungulates, the number of plants and soil erosion rates. He said while linking ungulate control to erosion control has been largely anecdotal so far, the research of he and other USGS scientists has pointed to some strong evidence.

“It seems there really is a connection between animal control, vegetation growth and erosion,” said Jacobi.

Tracking ‘Moonscapes’

Jacobi has focused his attention on “hot spots” on the Kawela mountainsides, which he described as “moonscapes” when his team fenced one as test site five years ago. He said these hotspots — natural areas of dirt and cinder deposites with little vegetation — account for 10 percent of the lowland Kawela landscape but are responsible for about 90 percent of sediment being washed onto the south shore reef.

In December 2008, his team noted less than one percent plant cover in one hotspot. They fenced an area less than one acre around the hotspot to exclude goats and a year later, vegetation inside the fence had increased to almost five percent. In 2009, goat control began in the area, and ungulate numbers went from more than 800 goats observed in 2009, down to less than 300 in 2012, according to Jacobi. Those numbers were also reflected in the plant growth inside and outside the fenced area. In April 2010, vegetation inside the fence had climbed to almost 25 percent coverage, while outside the fence had also increased to about 20 percent. The following April, growth in the fence reached 50 percent, and outside surpassed it at 55 percent.

There was one thing that surprised Jacobi about the results.

“There were mostly native species in the fences – I really didn’t even expect that,” he said. Given the opportunity, the natives spread and regenerated naturally.

“We both thought ‘no way, native vegetation won’t come back,’” said The Nature Conservancy Director of Molokai Programs Ed Misaki, who helped coordinate animal control efforts and worked closely with Jacobi during his research. “[The results] blow my mind.”

In addition to vegetation studies, Jacobi teamed up with other USGS scientists — some of whom wrote an extensive 2007 report on sedimentation of Molokai’s south shore reef — and used instruments to examine soil run-off and erosion rates. Those instruments installed on the Kawela mountainsides over a period of a few years included flow meters, soil moisture loggers, rain gauges and other that gave scientists valuable data. In addition to tracking erosion on the mountainside, scientists have also explored the amount of time it takes for a soil particle to be flushed from the reef once it reaches the ocean.

The answer is about 10 years, according to USGS researcher Mike Fields. So if efforts to prevent erosion continue, the reef could potentially become clearer in 10 years.

Using the mountain data they obtained, Jacobi said he and fellow researchers have created digital maps that can model various scenarios of vegetation growth, ungulate control, rain fall and other variables.

Turning Science to Action

Those models will help planners like Molokai’s Juanita Colon, general manager of Kawela Plantation. The homeowners association owns 5,200 acres of land above the Kawela residential areas and in 2011, members agreed to draft a plan to help preserve it, said Colon. Earlier this year, a three-year management plan was unanimously approved by homeowners.

The plan outlines seven goals, including reducing reef erosion, conducting feral animal and invasive weed control, protecting archeological sites, engaging in wild land fire management and fostering community and resource management partnerships. She said she hopes to work with a variety of local organizations to development a game management units and public hunting opportunities, as well as culturally-based groups such as the Aha Kiole to preserve historic sites and conduct excursions for Plantation members. In addition, Colon said she wants to support coastal and terrestrial research like Jacobi’s.

The management plan also includes management and public rental of the Kaoini (Del Monte) Park, and hopefully in the future, restoration of the Kaoini Fishpond that the homeowners association owns, according to Colon.

“We’ve always been passive, but hopefully now we can take a more active role,” she said.

Another effort, the East Slope Watershed Start-Up Management Plan, also made strides last week. The East Slope is a nearly 15,000-acre area of east Molokai owned by at least 15 different landowners, said Steph Dunbar-Co, a Molokai resident and organizer of the effort to preserve the watershed area. Dunbar-Co has been working closely with residents and landowners to develop the start-up management plan.

“It’s a movement,” she said, “for people to have water, forest, and food resources, and a connection to those resources.”

Last Friday, several landowners became the first East Slope signatories of the East Molokai Watershed Partnership memorandum of understanding to move forward with preserving the East Slope for future generations. The effort marks one of many around the island toward better understanding, appreciating and managing Molokai’s precious water resources.

Excellent!!

At last! Some sensible people talking… they seem to know what they talking about and the how to maintain our island, but unfortunately, all good things that come from these wise people have no “opportunities” for making big bucks for the rich-hungry guys in the world that can easily make it happen. The “good guy” medal is not enough for some. But I still hope there are people who will invest their millions to just save the world we live in.