All About Avocados

By Dayanti Karunaratne, Community Reporter

By Dayanti Karunaratne, Community Reporter

It’s looking to be a banner year for avocados, as farmers from Kalae to Waialua are seeing clusters of flowers in bloom. Upon walking amongst their trees, however, a curious realization occurs: some trees are full of fruit, while others are just beginning to flower. That’s because avocados have the longest flower-to-fruit times of any tropical fruit.

And that’s just the beginning of the marvelous world of avocados. In speaking with people who have spent years tending avocado trees, it’s clear that the diversity, especially in Hawaii, is so huge that some don’t care to talk about the type of tree. Haas, Beardsley, Greengold … a Google search will only get you so far. Better to “know your tree,” says Dano Gorsich at Waialua Permafarm.

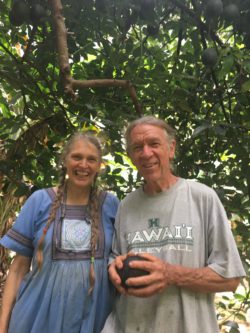

Together with his partner Robin, Gorsich has farmed in the east end valley since the early 1980s. Now, both Dano and Robin are certified permaculture instructors who tend to 13 avocado trees, which they call by name rather than species. There’s Frank, a one-of-a-kind variety that was grown from seed and is now about 35 years old. Dano calls Frank “a perfect tree” for its reliable bearing of great fruit. There are “siblings” Midden and Red Midden; the word midden is an archeological term for a place where remains of human activity have been found, and the historic site is now the happy home of two avocado trees, that were grown from seeds from the same tree. Like siblings, they are similar but have different characteristics.

It’s impossible to understand avocado fruit without understanding the unique pollination process behind it. All trees are either Type A or Type B; A-Type trees bloom with their female reproductive parts available first, in the morning. B-Type trees also open in the morning, but in their male phase. The following day, the blooms open for a second time, in the afternoon, expressing the opposite sex flower. While one tree flower can technically pollinate another flower on the same tree, it’s not ideal — especially if what you are after is delicious fruit. That means if you’re looking for a big harvest, you need a network: either multiple trees strategically placed or an area with multiple trees of Type A and Type B. You also need flies or another pollinator insect, but that never seems to be an obstacle for farmers on Molokai.

Having more than one tree — or a neighbor’s tree you can closely inspect — also tells farmers that their trees are “in sync” with each other, says Kyle Franks, who tends to a small farm in Kalae.

Franks, who has a Bachelor of Science in biology and plant physiology from Georgia Southern University as well as a certification in permaculture, relies largely on two mature trees — one is Type A and the other Type B — which are estimated to be over 70 years old. Last year, his Type B tree didn’t flower, which he attributes to the drought conditions. He’s also seen trees produce an abundance of not-that-great fruit; he interprets this as a survival technique, as the tree aims to continue its genetic line through the seeds.

“It’s the tree’s way of keeping itself alive, through seeds that will produce new trees,” he says.

This year the tree is bursting with flowers, and Frank’s careful pruning makes harvesting safe and relatively easy. About 45 feet away, there’s a Beardsley, which is a Type A variety, that is estimated to be over. Even at first glance the two trees look radically different. Franks notes that’s partly because the Beardsley sheds all of its leaves.

“It’s natural,” he explains, “it’s just mulching itself. Avocado feeds avocado.”

For farmers looking to sell, or anyone who wants consistent access to avocados, a tree that can hold ripe fruit on the branch for weeks is optimal. Plus, those varieties tend to have a higher fat content, as the fruit has a longer time to convert water to oil. Franks checks his fruit for readiness by bending it to a 90 degree angle: if it snaps off the stem easily, it’s ready. Or if the stem itself is breaking or cracking, if it maintains its togetherness, it’s not ready — some stems even change color as they ripen.

Those who have spent years around avocado trees have also learned how to detect, manage and avoid problems. A lack of fruit on a tree that’s over five years old could be due to a pollination issue — time to have a closer look at your network of avocados. Compact soil, termites and root rot are all problems facing avocado trees on Molokai. And farmers are in agreement that any tree grown from seed will be less productive than one grown by combining reliable root stock with a graft created from a tree known to be fruitful.

Glenn Teves with the University of Hawaii’s College of Tropical Agriculture and Human Resources Extension Service on Molokai notes that root rot is the biggest infection problem, but can be avoided as long as the tree is not over-watered at a young age. But if the entire plant, or even part of it appears to be dying, root rot could be the issue.

“Planting where you have no standing water is key,” says Teves. “Plant on slopes or on a high point in your yard can help. That’s why they grow well in Kona.” When transplanting to the field, he suggests minimal water, away from the base. “Make a round furrow six to 10 feet away from base. They don’t like wet feet.”

Whether you’re looking to grow your own tree, or are trying to get an existing tree to be more fruitful, there’s a wealth of knowledge on the island. And if you’re simply looking to enjoy more avocados, look for them on the Mobile Market of Sust’aina ble Molokai.

Don't have a Molokai Dispatch ID?

Sign up is easy. Sign up now

You must login to post a comment.

Lost Password